Guidance is the scientific procedure for assisting an individual. Various types of tools and techniques are used for measuring the potentialities of the individual the guidance purpose.

The following are the main tools and techniques which are employed in guidance services:

1. Observation Technique:

The observation technique is not frequently used in guidance and counselling. This is a subjective technique even it is indispensable techniques. For the children no other tool and technique can be used except the observation schedule.

Advantages of Observation:

Observation has certain advantages over the personality test as an approach to understanding children from the practical standpoint. Even hit-or-miss incidental observation gives one a ‘feeling’ for the child’s personality that the test score or even an analysis of the responses to the individual items cannot give. Observation is a relatively ‘free’ situation-one in which the pupils feel the absence of adult pressure-may reveal important aspect of the personality.

This possibility vanished, however, when the pupil knows he is under observation. Then too, observing does not interfere with the usual school activities as testing does. Finally, one can usually see how the child responds in social situations, and note how he reacts to frustrating situations.

Limitations of Observation:

Unfortunately there are many difficulties inherent in the process of observation. In addition to the fact that observation is a highly skilled technique, it is almost impossible for most teachers to spend enough time in observing to enable them to get a well-rounded picture of the child’s personality-in-action.

Errors of properly, or if the observer has no other knowledge of the child, misinterpretation of the meaning of his behaviour is frequent. Bias, of course, on the part of the observer will vitiate the result. In many situations, too, the child, particularly the older child or adolescent, will ‘cover up’ so as to conceal his true feelings. Finally, the same behaviour at different times may not have the same meaning.

Methods of Improving Observation:

Observation may be improved by keeping careful records of the behaviour, preferable writing the observation dawn at the time or, if that cannot be done, as soon afterwards as possible. It is important to pay particular attention to the setting and, if that is vague or equivocal, to forbear from recording the observation.

It is also helpful to record separately the direct observation and the inference drawn from it; this makes possible check by another person on the validity of the interpretation. Simultaneous observation with another capable person and comparison of records afterward is a good method of improving the quality and accuracy of one’s own work.

If the unit of observation are too short, will be highly reliable, but often unimportant observations are likely to be the result. One individual should be observed for measuring one variable at one time. The anecdotal record or check lists prepared in advance may be used.

The Diary Record Method:

Detailed observation of one child is usually for the purpose of comparison with other data already at hand, and to determine the kinds of situations in which he has difficulty. For this purpose a running diary account of the pupil’s behaviour is usually the most length of time and in a variety of situations.

The elementary child may be watched in class, on the playground, in the halls of the child, on the way home, and if possible in the home; the secondary pupil, in the home-room, in various classes, during examinations, in the study hall or library, at a club meeting, or in a child dance, in the child criteria, and in games or sports with his peers.

2. Interview Technique:

Another important technique is the interview technique which is used for collecting information’s about the individual by interview his parents and pears or other family members. It has also some limitations to have the reliable data.

Value of Information from Parents:

From the standpoint of diagnosis, there are two immediate reasons why parents should be seen by the elementary child teacher—to gather sufficient knowledge about a child to provide him with the most suitable educational experiences, and to obtain additional insight into the causes of the behaviour of the child who already has difficulties in adjustment.

The same two reasons apply to the secondary child teacher as well, although the problem of contacts with the parents of the adolescent is complicated by the implied reflection on his feeling of personal worth.

Information for the first of these purposes may sometime be obtained through a questionnaire plus short contacts after child affairs or parents teacher meeting. Although home visits are usually desirable, in most communities teachers do not have time to visit the homes of many of their pupils.

Suggestions for Conducting Interviews:

When the child has shown difficulties in adjustment, it is usually advisable for interviews to be held with at least one of the parents and preferably both. This is frequently difficult to arrange, in view of the many duties of the teacher and the parents, but it usually can be effected by some sacrifice on the part of both. The conference will be facilitated or hindered by the general attitude on the part of the parents toward the child, and by the community’s conception of the role of the teacher.

If the parents have a negative attitude toward the child, and if there is common belief that the teacher’s functions is that of drilling on the three R’s the teacher’s first job will be to establish a friendly attitude before further progress can be made. The teacher should also be alert to differences in cultural background between himself and the parents, to speak in laymen’s language and yet avoid ‘talking down.’

He must appreciate that many parents resent an inquiry into their personal affairs, and in dealing with the parents of problem children he should expect to find many who will be quick to interpret innocuous comments as placing blame on them.

In talking with the parents of young children he should be sensitive to a possible feeling of rivalry on the mother’s part, for the teacher is often the first adult outside the family circle to have an appreciable influence on the child.

Often, too, the parents feel that the child situation is the sole cause of the problem behaviour and that they themselves have no responsibility in the matter. It is particularly important for the teacher to convince the parents that confidence will be scrupulously respected.

3. The Cumulative Record:

The cumulative record means of keeping readily available permanent data about a child. These data in themselves are likely to aid the teacher in appraising the child’s assets and liabilities. The record can also serve as a source of new knowledge if an analysis of the meaningful relationships among the different items is made.

An especially complete record card includes spaces for the following:

i. Tests:

Intelligence and standardized achievement;

ii. Marks:

Elementary and high school;

iii. Home:

Occupation and nationality of parents, names and ages of siblings, languages spoken;

iv. Health:

Medical examination, physical development, defects, and treatment;

v. Prolonged absences, with causes;

vi. personality-short description by teacher;

vii. vocation-educational aim, vocational aim, special interests,

viii. Vocation-educational aim, vocational aim, special interests, outside employment, school activities;

ix. Records of conferences with pupil-important attitudes, remarks, and decisions.

One can easily see how such a record would provide a valuable basis for guidance of the student in selecting courses, curricula, advanced educational, and a vocational career. It is useful in understanding the maladjusted pupil chiefly as a source of clues for further inquiry. Obviously such a brief compilation of more or less objective data cannot include the type of information needed to understand the sources, and dynamic factors in, most pupil maladjustments.

4. Adjustment Inventory or Schedule:

Adjustment schedules are frequently called self-report blanks, adjustments questionnaires, or inventories. It is impossible to differentiate them clearly from ‘tests’ designed to measure such personality traits as introversion, self-confidence, etc., since most, if not all, aspects of personality are related to adjustment. The purpose of adjustment schedules is to estimate an individual’s degree of adjustment or maladjustment.

In their preparation, as series of questions designed to reveal attitudes, feelings and behaviour indicative of maladjustment is gathered, attempts are made to validate them and they are administered to a representative group, norms are established. Thus, when the inventory is subsequently administered to an individual, the degree of maladjustment indicated by these responses can be compared with those of the original group.

Uses of Adjustment Inventory:

Adjustment inventories cannot yield conclusive assessment due to the following reasons:

i. It is difficult to formulate diagnostic questions which are understood by all and have the same meaning for all.

ii. It is not possible by the use of the inventories which limits to true or false; it is an inventory to expose the extent of adjustment.

iii. An adjustment inventory can be validated.

iv. It is not the reliable. It cannot differentiates.

v. It depends on frankness of the subject in responding.

The adjustment inventories are useful in school situations may be summarized as follows:

i. For identifying some of the pupils needing special aid in adjustment. Those who need help but cannot bring themselves to answer the questions frankly will, of courses, have been located through some other means.

ii. For uncovering unsuspected personal problems through noting an pupil’s answers to the specific questions. The existence of such problems must then be verified through other techniques.

iii. For discovering clues to the basis of the adjustment difficulty by means of a thorough analysis of the answers.

iv. For confirming a suspected maladjustment of a pupils when other evidence yields inconclusive data. (A low score, however, would leave the issue undecided).

Types of Adjustment Inventories:

The adjustment inventories are related to different areas—Home, Health, Social, emotional and School.

These inventories are of the following types:

(i) For elementary child pupils.

(ii) For high child students, and

(iii) For college students or adults.

5. The Case Study:

The case study is the most comprehensive of all methods of special inquiry for use with maladjusted children or with those who exhibit unusual but undeveloped abilities. Such a study is often made by a specialist, though teachers are finding an increasing need to use this device in the course of their professional work.

The case study is employed in a variety of situations. It is an attempt to synthesize and interpret the material gathered by the other techniques for the purpose of making an inclusive picture of the individual and of the background factors affecting his life.

Items of Include in a Case Study:

The amount and kin of information in any one are varies greatly in accordance with its relevance to the particular individual studied, the adequate case study will, with certain exceptions, include information in the nine areas listed below. In accordance with its relevance to the particular individual studied, the adequate case study will, with certain exceptions, include information in the nine area listed below.

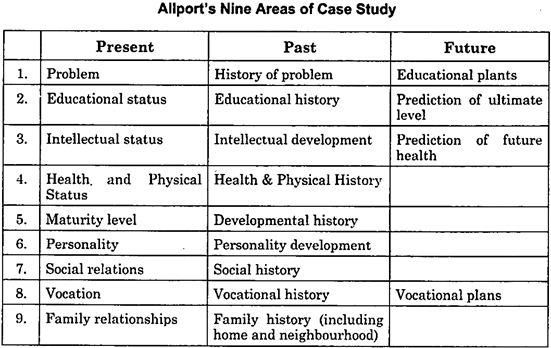

In accordance with Allport’s suggestion that “successful case studies seem naturally to fall into three sections – (a) A description to the present status, (b) An account of past influences and successive stages of development, and (c) An indication of future trends,” the topic have been arranged in that fashion.

Allport’s Nine Areas of Case Study:

Suggestions for specific items in the areas must of necessity be tentative. So many variable affect the nature of the information gathered—age, sex, type of problem, to mention but a few-that inevitably some irrelevant items are included and many relevant items are omitted. An attempt has been made to be inclusive rather than brief because many case studies made by teachers and other workers in child have come to erroneous or unsure conclusion owing to the commission of items crucial to understanding the case.

Steps in Conducting a Case Study:

Case studies usually begin with certain identifying data. These include the child’s name, address, age, sex, grade, nationality, colour and religion.

Frequently, too, a very brief description of his physical appearance and a thumbnail sketch of his personality are included. The purpose is to orient the reader or to recall that particular child to the writer of many case studies.

The next topic covered should be the problem, but after that the order of topics depends upon the specific case investigation.

The following information’s are to be collected:

a. Problem at present,

b. Education at present,

c. Intelligence,

d. Health and physical conditions,

e. Development at present,

f. Personality make up,

g. Social adjustment,

h. Educational status if any, and

i. Family conditions-economic and cultural level.

This material should enable one to judge whether the problem originated in the home, the child, or both. In this area one is especially likely to find background material that goes a long way to explain the child’s behaviour.

The Case Study Materials:

In child the best procedure in starting a case study is to assemble the information already collected on the child. The cumulative record, if available, should be consulted first. Usually it is necessary to arrange for tests as the ones on file are not likely to be recent enough. If there is the slightest indication of a physical basis for the problem, a thorough medical examination should be made.

The usual medical examination by the child physician is almost certain to be too superficial to be of much use. Interviews should usually he held with the parents, and the child should be observed in as many situations as can be arranged. Interviews with the child are essential, as only through this means can one establish the type of relationship necessary for understanding the problem and aiding readjustment.

A Diagnosis:

After the material considered pertinent is gathered, there must be an attempt to synthesize; it by comparing the information in the different sections and interrelating it. The purpose is to make a diagnosis, which may be defined as a description of the maladjustment together with the causative factors in both the past and present.

The process is exceedingly difficult; it frequently happens that even when the expert draws on all the psychological and social knowledge at his command he still finds that the case remains unexplained. Certainly the teacher in attempting a diagnosis must use the knowledge of his own motivation and his experiences with other, taking what precautions he can against his own bias.

Remedial Measures:

All the methods of approach to understand the child, constitute at the same time an opening for the prevention of maladjustment. It is through such methods that the teacher can acquire the knowledge of the child’s particular assets and liabilities and of the factors at the basis of his difficulty which are indispensable to the proper use of corrective procedure assets and liabilities and of the factors at the basis of his difficulty which are indispensable to the proper use of corrective procedures.

General prescriptions for handling children’s problems must be of limited value; only the person who understands the specific child can judge whether or not the suggested method of handling is wise or unwise.