In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Concept of Classical Conditioning 2. Process of Classical Conditioning 3. Laws.

Concept of Classical Conditioning:

Classical conditioning gets its name from the fact that it is the kind of learning situation that existed in the early “Classical” experiments of Ivan Pavlov (1849- 1936). In the late 1890s, the famous Russian physiologist began to establish many of the basic principles of this form of conditioning.

Classical conditioning is also sometimes called respondent conditioning or Pavlovian conditioning. Pavlov won the Nobel Prize in 1904 for his work on digestion. Pavlov is remembered for his experiments on basic learning processes.

Pavlov had been studying the secretion of stomach acids and salivation in dogs in response to the ingestion of varying amounts and kinds of food. While doing so, he observed a curious phenomenon: Sometimes stomach contraction, secretions and salivation would begin when no food had actually been eaten.

The mere sight of a food bowl, the individual who normally brought the food, or even the sound of that individual’s foot steps are enough to produce a physiological response in the dog. Pavlov’s genius research was able to recognize the implications of this rather basic discovery.

He saw that the dogs were responding not only on the basis of biological need but also as a result of learning or as it came to be called, classical conditioning. In classical conditioning, an organism learns to respond to a neutral stimulus that normally does not bring about that response.

To demonstrate and analyze classical conditioning, Pavlov conducted a series of experiments. In one, he attached a tube to the salivary gland of a dog. He then sounded a tuning fork and just a few seconds later, presented the dog with meat powder.

This pairing was carefully planned so that exactly the same amount of time lapsed between the presentation of the sound and the meat powder occurred repeatedly.

At first the dog would salivate only when the meat powder itself was presented, but soon it began to salivate at the sound of the tuning fork. In fact, even when Pavlov stopped presenting the meat powder, the dog still salivated after hearing the sound. The dog had been classically conditioned to salivate to the tone.

Process of Classical Conditioning:

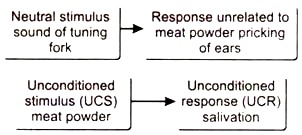

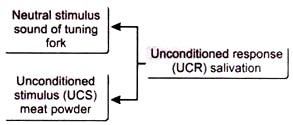

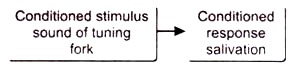

The figure below shows the process of classical conditioning:

(a) Before Conditioning:

(b) During Conditioning:

(c) After Conditioning:

Figure (a):

Consider the first diagram. Prior to sound of a tuning fork and meat powder, we know that the sound of tuning fork leads not only to salivation but also to some irrelevant response such as pricking of the ears, the sound in this case is therefore called the neutral stimulus because it has no effect on the response or interest.

We also have meat powder, which because of the biological makeup of the dog, naturally leads to salivation of the response that we are interested in conditioning. The meat powder is considered as unconditioned stimulus or UCS, because food placed in a dog’s mouth automatically causes salivation to occur.

The response that the meat powder elicits (salivation) is called an unconditioned response or UCR, a response that is not associated with previous learning. Unconditioned responses are natural because they are innate responses that involve no training. They are always brought about by the presence of unconditioned stimuli.

Figure (b):

Illustrates what happens during conditioning. The tuning fork is repeatedly sounded. Just before presentation of the meat powder, the goal of conditioning is for the tuning fork to become associated with the unconditioned stimulus (meat powder), and therefore, to bring about the same sort of response as the unconditioned stimulus. During this period, salivation gradually increases each time the tuning fork is sounded, until the tuning fork alone causes the dog to salivation.

Figure (c):

When conditioning is complete, the tuning fork has evolved from a neutral stimulus to what is now called a conditioned stimulus or CS. At this time salivation that occurs as a response to the conditioned stimulus (tuning fork) is considered as a conditioned response or CR. This situation is seen in figure (c) after conditioning, then the condition stimulus evokes the conditioned response.

The sequence and timing of the presentation of the unconditioned stimulus and the conditioned stimulus are particularly important. A neutral stimulus that is presented just before the unconditioned stimulus is most apt to result in successful conditioning.

Research has shown that conditioning is most effective if the neutral stimulus (which will become a conditioned stimulus) precedes the unconditioned stimulus by between a half second and several seconds, depending on what kind of response is being conditioned.

Laws of Conditioning:

The laws that characterize classical conditioning are as follows:

1. Acquisition:

Each paired presentation of the CS and US is called a trial and the period during which the organism is learning the association between the CS and US is the acquisition stage of conditioning. The time interval between the CS and US may be varied.

In simultaneous conditioning, the CS begins a fraction of a second or so before the onset of the US and continues along with it until the response occurs.

In delayed conditioning, the CS begins several seconds or more before the onset of the US and then continues with it until the response occurs.

In trace conditioning, the CS is presented first and then removed before the US starts (only a “neural trace” of the CS remains to be conditioned).

In delayed and trace conditioning the investigator can look for the conditioned response on every trial because there is sufficient time for it to appear before the presentation of the US, thus if salivation occurs before the delivery of food we consider it conditioned response to the CS, any number of CS can be presented before US.

In simultaneous conditioning the conditioned response does not have time to appear before the presentation of the US and it is necessary to include test trials— trials on which the US is omitted to determine whether conditioning has occurred. For example, if salivation occurs when the CS is presented alone, we consider that conditioning has occurred. Delayed conditioning experiments indicate that learning is fastest if the CS is presented about 0.5 seconds before the US.

With respected paired presentations of the CS and US, the conditioned response appears with increasingly greater strength and regularity, the procedure of pairing the CS and US is called reinforcement, because any tendency for the CS to appear is facilitated by the presence of the US and the response to it. Inflection stands for stimulus onsets. Deflections represent terminations.

2. Extinction:

If the unconditioned stimulus is omitted repeatedly (no reinforcements), the conditioned response gradually diminishes. Repetition of the conditioned stimulus without reinforcement is called extinction. Unlearning what we have learnt, extinction occurs when a previously conditioned response decreases in frequency and eventually disappears.

To produce extinction, one needs to end the association between conditioned and unconditioned stimuli. For example, If we had trained a dog to salivate at the sound of a bell we could produce extinction by ceasing to provide meat after the bell was sounded.

At first the dog would continue to salivate when it heard the bell, but after a few such instances, the amount of salivation would probably decline and the dog could eventually stop responding to the bell altogether. At the end point, we could say that the response had been extinguished. It seems extinction occurs when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus.

3. Spontaneous Recovery:

The return of the conditioned response once a conditioned response has been extinguished but it has not necessarily vanished forever is called spontaneous recovery. Spontaneous recovery is the reappearance of previously extinguished response after a considerable time has lapsed without exposure to the conditioned stimulus.

4. Generalization and Discrimination:

Stimulus generalization is response to a stimulus that is similar but different conditioned stimulus, the more similar the two stimuli, the more likely generalization is to occur. Stimulus discrimination is the process by which an organism learns to differentiate among stimuli restricting its response to one in particular.

5. Higher Order Conditioning:

Higher order conditioning occurs when a conditioned stimulus which has been established during earlier conditioning is then paired repeatedly with a neutral stimulus. If this is neutral, by itself comes to evoke conditioned stimulus, higher order conditioning has occurred. The original conditioned stimulus acts in effect as an unconditioned stimulus.

6. Operant Conditioning (Instrumental):

Operant conditioning describes learning which is weakened depending on its positive or negative consequences. Unlike classical conditioning in which the original behaviours are the natural biological responses to the presence of some stimuli such as food, water or pain, operant conditioning applies to voluntary responses, which an organism performs deliberately in order to produce a desirable outcome.

The term “operant” emphasizes this point. The organism operates on its environment to produce some desirable results. For example, operant conditioning is at work when we learn that studying hard results in good grades.

In the 1930s’ BF Skinner began his influential experiments on what he termed operant conditioning. He termed the “Skinner box” or as it is often called the “operant chamber”. An operant chamber is a simple box with a device as a lever for pigeons; the device is a small panel called a “key” which can be pecked.

The lever and key are activated when positive reinforcement is being used as food delivery or water delivery mechanism. Thus positive reinforcement is contingent upon pressing a lever or pecking a key. Since these responses are positively reinforced they increase in frequency.

Suppose you want to teach a hungry pigeon to peck a key that is located in its box. At first the pigeon will wander around the box, exploring the environment in a relatively random fashion. At some point, however, it will probably press the key by chance and when it does, it will receive a food pellet. The first time this happens, the pigeon will not learn the connection between pressing and receiving food and will continue to explore the box.

Sooner or later the pigeon will again press the key and receive a pellet and in time the frequency of the pecking response will increase. Eventually, the pigeon will peck the key continually until it satisfies its hunger, thereby demonstrating that it has learned that the receipt of food is contingent on the pecking behaviour, reinforcing desired behaviour.

Skinner called the process that leads the pigeon to continue pecking the key “reinforcements”. Reinforcement is the process by which a stimulus increases the probability that a preceding behaviour will be repeated. In other words, pecking is more likely to occur again due to the stimulus of food.

In a situation such as this one, the food is called a reinforcer. A reinforcer is the only stimulus that increases the probability that a preceding behaviour will occur again. Hence food is a reinforcer because it increases the probability that the behaviour of pecking the key will take place.

A primary reinforcer satisfies some biological needs and works naturally regardless of a person’s prior experience. Food for the hungry person, warmth for the old person are primary reinforcers.

A secondary reinforcer is a stimulus that becomes reinforcing because of its association with a primary reinforcer. For instance, we know that it allows us to obtain other desirable objects including primary reinforcers such as food and shelter. Thus money now becomes secondary reinforcer.

7. Positive reinforcement:

A positive reinforcer is a stimulus added to the environment that brings about an increase in the response that preceded it. If food, water, money or praise provided following a response, it is more likely that the response will occur again in the future, the pay check that workers get at the end of the week, for example, increases the livelihood they will return to their jobs in the following week.

8. Negative reinforcement:

Negative reinforcer refers to a stimulus that remain something unpleasant from the environment, leading to an increase in the probability that a preceding response will occur again in the future.

For example, If you have cold symptoms that are relieved when you take medicine you are more likely to take the medicine (a negative reinforcer) when you experience such symptoms again. Like positive reinforcer, negative reinforcement occurs in two major forms of learning, Escape conditioning and avoidance conditioning.

In escape conditioning, an organism learns to make a response that brings about an end to an aversive situation. For example, busy college students who take a day off to elude the stress of too heavy workload, are showing escape conditioning.

In contrast to escape conditioning, avoidance conditioning occurs when an organism responds to a signal of an impending unpleasant event in a way that permits its evasion. For example, automobile drivers learn to fill up their gas tanks in order to avoid running out of fuel.