After reading this article you will learn about the scientific views on intelligence based on empirical evidence.

Measurement-Based Views on Intelligence:

One of the earliest psychologists who studied the problem of intelligence was E.L. Thorndike, who is much more known for his work on the trial and error theory of learning and his epoch-making and ingenious experiments with cats.

According to Thorndike, intelligence involves a combination of abilities, some of which are motor and involve muscle operations, some involving the use of numbers, images, words etc. Further, intelligence, particularly at the human level is reflected in our interaction with others also. Intelligent people get along better with others and are able to establish themselves in groups.

Accordingly Thorndike postulated that intelligence is a complex ability operating at three levels. The first is the mechanical level which relates to the ability to manipulate things, employ tools effectively, etc. This level can be easily seen even in animals. Many of these abilities could be acquired through learning.

The second is the abstract level which involves imagination, thinking, the use of numbers, responding to speech, use of language, etc. These are clearly seen in the case of the human being and even in some of the more developed animals. Thus experiments have shown that monkeys are capable of learning the use of symbols, tokens, etc.

However, at the third level, the social level is more typical of the human beings and is essential to understand others, getting along with them, etc. The reader can easily appreciate the importance of this level for human life, Thorndike further observed that many operations involve more than one level.

A student studying engineering subject or computer sciences will find that both concrete and abstract levels of operations are involved. Similarly students in courses like public relations, marketing, business management and other courses will have to function at the social level also.

However, it may be seen that as society advances technologically and socially, abstract and social level operations acquire more and more importance. Individuals, according to Thorndike, differ on all these levels or types of intelligence.

Later views on intelligence while not strictly agreeing with Thorndike’s concept of levels of intelligence nevertheless have developed tests to measure mechanical, abstract and social dimensions of intelligence. Thorndike was also a pioneer in the development of tools for measurement of intelligence.

Spearman and the Two-Factor Theory of Intelligence:

The credit for arriving at a very systematic and scientific analysis of the concept of intelligence based on an analysis of scores of a large number of people on a large number of intelligence tests goes to the British psychologist Charles Spearman. Spearman found that a number of intelligence tests had been developed and extensively used without being clear about what was being tested and scored.

Assuming that all these tests were measuring intelligence, Spearman wanted to know what type of abilities and how many abilities they were measuring, based on the degree of relationships among the scores obtained by a large number of individuals (correlations) on a large number of tests, employing a mathematical method called factor analysis.

Accordingly, he arrived at the following findings:

(a) Every intelligent activity involves a factor common to all the activities called the general factor or “g.”

(b) In addition, every activity also involves something specific to it called the special factor “s”.

(c) In view of this, it may be concluded that what we call intelligence is the “g” factor which varies from person to person.

(d) Where an activity involves more of motor and physical action, and is routinized, the “s” factor assumes a greater role.

(e) The “g” factor according to Spearman can be taken as the general cortical or neural energy at the disposal of the individual. Since the role of cerebral activity becomes less and less with practice and also with more mechanical action, such actions are not suitable for measuring intelligence, “g” factor has a greater role to play in activities which are called neo-genetic or which result in “generation of new knowledge” and less dependent on memory.

Thus learning a road route from a map, understanding a general scientific principle by reading a book, etc., involve more “g” than merely working out the same type of arithmetic problems or reciting the same poem again and again.

According to Spearman, apprehension of a new experience, analyzing the relationships among the various elements of the experience and on the basis of the experiences concluding what is likely to happen, are the basic abilities involved in “g”.

An intelligent detective understands the various elements in a crime situation, tries to relate them, and on the basis of these comes to certain conclusions about the perpetrator of the crime. According to Spearman, “g” is involved in apprehension of experience, education of relations and education of correlates.

Spearman also held that “g” is innate and is influenced by a number of factors like age, sex, heredity etc. Spearman also suggested the existence of “group factors” like verbal ability, numerical ability, etc., which enter a group of related and similar activities though he did not emphasize them much.

Contemporary textbooks in psychology generally do not discuss Spearman’s view in detail, especially the American texts. But the credit for arriving at the first systematic and scientific formulation of a theory of intelligence goes to Spearman. His theory even changed the nature of tests of intelligence.

Thurstone’s Views on Intelligence:

Many psychologists, however, were critical of Spearman’s views. One leading psychologist among them was L.L. Thurstone of the Chicago University, United States. According to Thurstone there is no general factor or “g” which is measured by intelligence tests. He was critical of the particular procedure of factor analysis employed by Spearman.

Employing a different technique of factor analysis on the scores of a large number of people on different intelligence tests, Thurstone arrived at his theory of primary mental abilities. He postulated a number of primary mental abilities.

Thurstone arrived at the following terms of primary mental abilities:

(a) Numerical ability:

N – The ability to deal with numbers and manipulate them.

(b) Reasoning ability:

R – The ability to apply logic like induction and deduction and arrive at conclusions or solutions, given a series of related situations.

(c) Verbal fluency:

W – Competence in Language and the Use of Words, fluently – the ability to translate procedures and factors and ideas into languages which in turn promote better reasoning.

(d) Verbal comprehension:

V – Apart from the ability to use and deal with words, the ability to understand material presented in the form of words.

(e) Perceptual ability:

P – The ability to perceive situations which are complex with a variety of elements, and organise them in order to arrive at a meaningful perception.

(f) Memory:

M – The ability to remember facts, situations, experiences, etc. which often become relevant to solve a problem or answer a question in the present.

(g) Spatial ability:

S – This relates to the ability to organise space and the stimulation coming from different directions, coordinate the same and integrate one’s behaviour.

Here one may assume that the term “space” means not only physical space but also psychological space, experiences and events which occurred at different times and in different contexts. Thurstone, on the basis of his analysis of scores on different tests of intelligence, argued that the “g” factor arrived at by Spearman was a result of correlations among the measures of these various primary abilities, and is not primary.

Cattell’s Views on Intelligence:

R B Cattell, an outstanding psychologist questioned Thurstone’s analysis and argued that there is definitely a “g” factor as claimed by Spearman. However, according to Cattell there are two kinds of “g” factors. The factors are labelled by him as fluid intelligence or (g f). This “g” is a basic capacity to analyse, remember, understand and arrive at inductive and deductive findings, arrive at solutions to problems and in general learn in new situations.

The other “g” factor named as crystallized intelligence (g c) takes the form of specific abilities like verbal ability, numerical ability, etc. The crystallized intelligence emerges as a result of repeated experiences in the application of fluid intelligence and in that sense therefore, is acquired.

We may consider crystallized intelligence as “channelized or conditioned fluid intelligence” developed as a result of experience, in other words learnt. It is but natural that people with more fluid intelligence are likely to gain more of crystallized intelligence. This view suggests that “g” is innate and varies from individual to individual.

It may be seen that Cattell’s views bear a strong similarity to the views of Spearman. Fluid intelligence is essentially biological and free from experiential influences. Fluid intelligence may be said to reflect the capacity or potentiality while crystallized intelligence may be regarded as capacity or potentiality translated into actual ability as a result of practice, in short make use of what has been learnt. Cattell’s views thus attempted at an integration between learning and intelligence which no sensible theory of intelligence can afford to avoid.

One may see here that while Spearman and Thurstone were primarily measurement psychologists, Cattell had a more inclusive and total perspective view of human behaviour. Cattell’s explanation of the nature of intelligence reflects his deep interest in analysing and understanding human behaviour, intelligence being only one of the many major functions.

Jensen’s Views:

A.R. Jensen presented yet another view of intelligence. According to Jensen, “Intelligence” is essentially another activity or function of the individual like blood pressure, temperature, etc. Thus as a sphygmomanometer and a thermometer give us measures of blood pressure or body temperature, intelligence tests also give us a measure of intelligence, and therefore there is no need to multiply the same.

However, there is a difference between intelligence and the other functions. Normally at a particular time, if blood pressure and the body temperature are measured with instruments, we get very nearly the same results. This often is not found to be the case with intelligence, where it is found that different tests at the same time, give different scores.

This is because intelligence unlike the many other life functions is multidimensional and as different tests measure different dimensions we get different scores. Thus if different tests which measure different dimensions are administered to an individual and an attempt is made to place him, in a continuum ranging from low to high, one comes across certain inconsistencies.

According to Jensen, there are two factors of intelligence, breadth, and altitude. The former includes general information, vocabulary, etc., which are directly dependent on a person’s experience, exposure, and opportunities which a person has had. Environmental influences, as well as attitudes and interests acquired by an individual in the course of his life have their own influence on the breadth of a person’s intelligence.

In a way one can see a resemblance between Jensen’s concept of breadth of intelligence and Cattell’s concept of crystallized intelligence, though the former is more general, and not perhaps crystallized. The other factor altitude, however, according to Jensen is more innate and less dependent on environmental influences, again leaving a resemblance to Cattell’s concept of fluid intelligence.

On the basis of a number of studies, mainly based on children and minority groups, relating to cognitive processes, Jensen came to the conclusion that there are two different kinds of abilities which are independent and yet related. These two abilities are known as associative ability and cognitive ability.

These two abilities are genetically determined and depend on different genetic factors, and therefore their rates of development differ from one person to another. According to Jensen most of our intelligence tests basically measure these two abilities. Tests like Free recall, Digit span. Serial learning, etc., measure associative ability, while tasks involving concept formation, and abstract reasoning, patterns formation, mathematical reasoning, etc. measure cognitive ability.

One may again see, a similarity between Jensen’s views and the views of others, this shows that there is evidence from different quarters pointing to certain repetitive and similar findings. But still, no conclusive inferences have been arrived at.

J. P. Guilford, a leading psychologist and also a pioneer in the field of psychological measurement, came out with an actual structural concept or model of intelligence. In a way Guilford’s model may be described as a model of the “intellect rather than intelligence.” While the term intelligence essentially connotes the ability to solve a certain problem or components of such an ability, the term intellect goes beyond this.

Intellect is not just an ability but a major functional unit of the mind. In a way we may describe it as that part of functional unit of the mind which deals with problems like perceptual thinking, learning, problem-solving, etc.

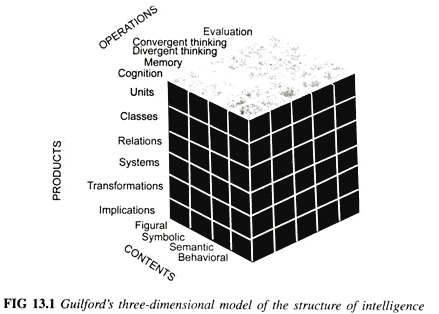

Guilford basically distinguished three categories which enter into any mental or intellectual operations. These are operations, (capabilities like thinking), contents (images, words, symbols, etc.) and products (new ideas, meanings, etc.) which emerge as a result of certain operations acting through certain contents.

Thus when we are solving a mathematical problem, we operate through thinking, in terms of contents which are numbers or mathematical signs or formulae, and arrive at solutions and products. Every intellectual operation involves the three. Further each of these categories or elements involves certain factors.

These factors are shown in the following figure:

Thus one finds that at least one factor in each category is involved in any intellectual operation. For example, if you are reading a newspaper article relating to a topic of your interest, the operations like reading, your memory of what you have learnt earlier about that topic, your comparative analysis and evaluation of the views explain in an earlier newspaper article come into action.

You may even find that you have missed some earlier articles of the newspaper and therefore you are not understanding – operations of evaluation, also comes into act. You may also find that a number of articles or other papers either express the same view or different views – convergent and divergent thinking.

In carrying out these operations, you use images, numerical data, and other forms, of contents. At the end of the reading you may arrive at new ideas, findings, conclusions, and other products. You may also begin to appreciate the implications which are products. Thus we find that all the three categories come into operation. However, the importance of these may vary from activity to activity.

For example, if a scientist is intending to discover some phenomenon which has not been studied so far, operations and products between them are more important. On the other hand if a student of art intends to understand whether some psychoanalytic processes find expressions in visual arts or literature, then the content becomes important.

Guilford’s model is not just a model of intelligence. It is almost a model of cognitive or even mental functions whereas the other models are purely conceptual models or measurement models of intelligence. This model is much more complicated and analytical while most of the other models have been descriptive.

However, before we do that it may be worthwhile to highlight some of the issues raised by these models:

1. The first and foremost issue that stands unanswered, is whether there is some general factor or master ability which may be identified as intelligence.

2. Arising from the above is the question of measuring and testing intelligence. Should we design tests to measure a ‘g’ or a test to measure a model of equally important abilities or a test to measure a ‘g’ factor, a group factor or primary abilities and a specific factor in hierarchical order?

3. How far is intelligence attributable to genetic and innate factors and how far is it attributable to certain environmental and experiential factors? This raises questions as to how far tests developed in one cultural setting are applicable in other cultural setting.

4. Deriving from Guilford’s model, one can also raise questions on what type of operations and what type of contents are to be used. Should we use verbal items or non-verbal items? Should we look for correct solutions (convergent thinkers) or trial and error solutions (divergent thinkers)? We may raise a number of such issues. But, even these few issues raised above appear to be formidable enough to keep psychologists thinking or stop thinking for a long time.